Molly has chosen to never grow up, postponing adulthood for as long as possible, whereas Ray grew up too fast. Molly’s unflagging brightness and Ray’s grim cynicism are both completely earnest reactions to having been pushed into a position where they must parent themselves throughout childhood, and into young adulthood, in Molly’s case. “Alert the media,” is Ray’s caustic response. Molly can’t believe that Ray has never been to Disneyland. Molly constantly greets the world with a naive optimism, while Ray is already jaded at age eight “It’s a harsh world,” sounds more like the motto of a weathered divorcee, not a private elementary school kid. She’s beyond vigilant about germs, she exclusively listens to classical music and she seems perfectly capable of running her own life without Molly around. “Precocious” is not a strong enough word to describe Ray’s behavior. Ray, on the other hand, is a tiny adult in ballet clothes. Molly is a mess, and runs her life like a tall child: She has a pet pig named Mu, she naps all the time, her whole apartment screams “health hazard” and she has a very sparing grasp on finances. The losses of their parents have affected their lives in two very separate ways. But when Molly and Ray first meet, it is difficult for them to see their similarities because they are much more defined by their differences. Ray’s life has been touched by tragedy as well: Her father has been in a coma for as long as she can remember, and her mother Roma (Heather Locklear), a high level music executive, hardly gives her the time of day. Even though she has no skills and now no money, Molly is determined to stay positive.

Molly is forced to move in with the only person willing to help-her controlling best friend Ingrid (Marley Shelton)-and take a job as a nanny to our fairy tale’s second princess, Ray (Dakota Fanning). Everyone wants something from the rock star princess, and they’re pretty shameless about it, until she’s destitute. Right off the heels of her 22nd birthday, another tragedy strikes her manager has run away with her fortune, leaving her penniless. She doesn’t have to work, thanks to her nepo baby trust fund that she’s been cruising on after the unfortunate deaths of her rock star parents in a shocking plane crash. As Uptown Girls opens, Molly Gunn (Brittany Murphy) lives a fairy-tale life, in both its idyllic nature and its inherent tragedy. Molly and Ray’s story is a remarkable one because they are complete personality opposites, yet able to connect with each other on a deeper emotional level than they can with anyone else.

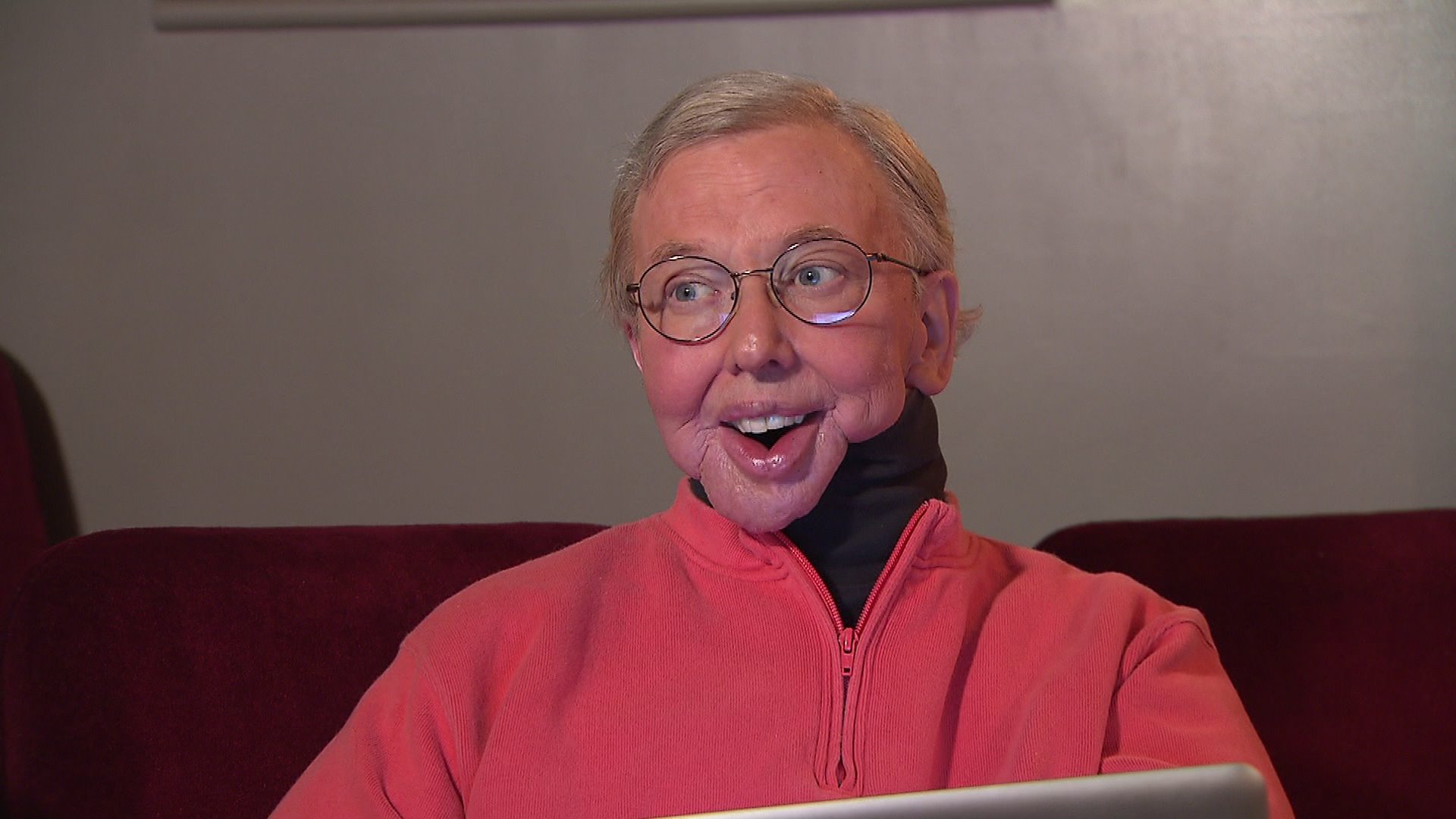

ROGER AND EBERT MOVIE

In his 3-star 2003 review, Roger Ebert defended the film against its haters, dismissing “all cavils about the movie’s logic and plausibility as beside the point,” asserting that “this is not a movie about plot but about personalities.” Ebert was able to see and hear Molly and Ray as vastly different, but equally emotionally complex characters, in a way that his peers were blind to at the time. Uptown Girls was shot by legendary New York City cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, who has also photographed the city for heavyweights like Martin Scorsese and Mike Nichols. Uptown Girls goes to darker emotional places than most other light hearted “chick flicks” of the early 2000s, and features career-best performances from Brittany Murphy and Dakota Fanning, as well as cameos from aughts superstars Mark McGrath and Nas. Sure, the plot is far-fetched, and the ending in particular is wrapped up in a nice, convenient little bow, but Uptown Girls is a unique story about what young women can learn from each other. It’s past time for Uptown Girls, almost universally panned when it first hit theaters 20 years ago, to be widely reconsidered and celebrated as a Y2K New York City fairy tale. Thus, Uptown Girls, the story of party girl Molly Gunn and her uptight little hypochondriac charge Ray, was born. Director Boaz Yakin, at the time best known for his 1994 Samuel L Jackson vehicle Fresh, wasn’t the most obvious choice to direct the overtly feminine story, but he connected with the characters and understood the singular style of comedy. She presented her idea to writers and producers at Greenestreet, who immediately loved her vision of a dead rock star’s daughter fallen from grace after her fortune was stolen from her. While working as a receptionist at Greenestreet Films, writer Allison Jacobs was struck with inspiration by classic New York films like Annie Hall and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, as well as her own personal nannying experiences.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)